In 2013, cirrhosis was responsible for 1.2 million deaths worldwide, not even taking into account more than 750,000 liver cancer deaths, mainly developing due to liver cirrhosis. While most cirrhosis patients initially do not show symptoms, acute decompensation of cirrhosis, defined as the body’s inability to cope with the progressing dysfunctionality of the liver, leads to drastic symptoms. Decompensation is characterized by the development of ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice, and/or gastrointestinal haemorrhage, and is often a turning point for a cirrhosis patient: The average life expectancy of a patient with compensated cirrhosis is 10 to 13 years, compared to only 2 years if decompensation occurs. Within 1-3 months, acute decompensation of cirrhosis is associated with a high risk of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF, 11% at day 28) or death (5% at day 28, and 14% at day 90). ACLF is characterized by failure of one or several major organs or systems (liver, kidney, brain, coagulation, circulation, respiration) and very high mortality rates (33% at day 28, and 50% at day 90), meaning that ACLF is by large the main cause of death in decompensated cirrhosis.

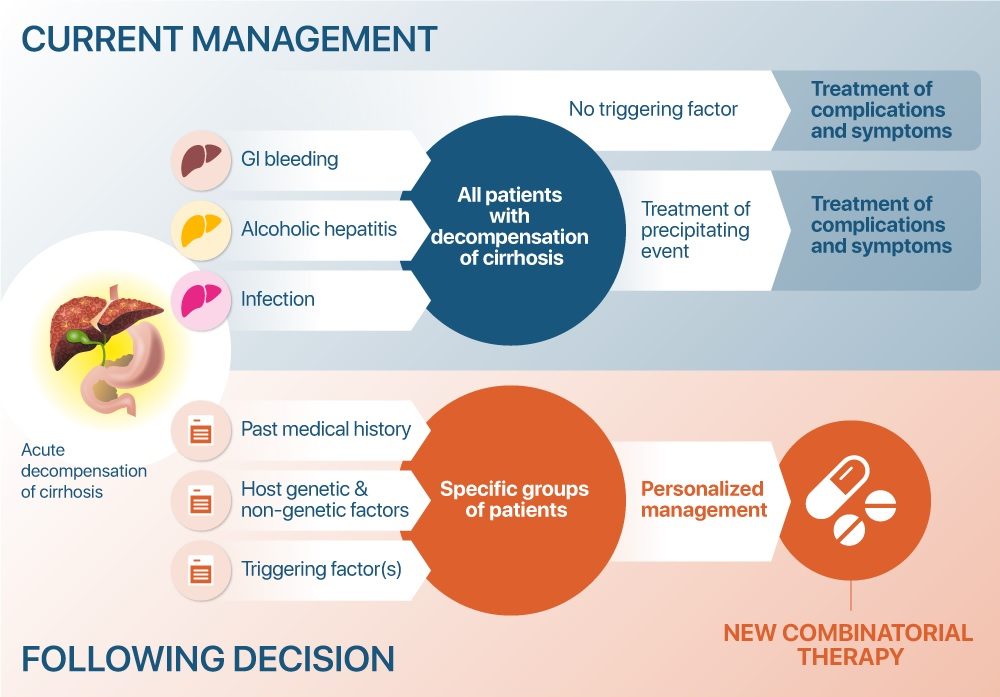

The fact that some patients suffering from decompensated cirrhosis recover, both many others die so fast is both tragic and baffling because numerous treatments targeting specific aspects of the disease are already available, such as absorbable intravenous and oral antibiotics, oral non-absorbable antibiotics, antiviral agents, albumin, laxatives, diuretics, non-selective beta-blockers, vasoconstrictors, statins, anticoagulants, steroids, and proton-pump inhibitors. The fatal difference in the patients’ response to treatment is likely explained by the large inter-individual variability of precipitating events and clinical presentations, but also by the fact that important factors involved in the pathophysiology of decompensation of cirrhosis have likely been overlooked so far. This clinical heterogeneity calls for novel and personalised combinatorial therapies according to underlying mechanisms based on each patient’s genetics, gender, disease history, and physiology.

This is where DECISION comes in: The research consortium will perform multi-omic profiling of already existing large and clinically well-characterized patient cohorts, including 2200 patients with readily available standardised biobank samples. The gained knowledge will enable the development of a prognostic and a response test, and allow for novel combinatorial therapies tailored to mechanism-based groups of patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. The ultimate goal is, of course, to reduce the risk of short-term death following acute decompensation of cirrhosis as much as possible.

Current treatment of acute decompensated cirrhosis versus personalised treatment of specific groups of patients with novel combinatorial therapies following the DECISION project.